How government monetary policy erodes the value of money

Why businesses across the globe are turning to Bitcoin as a store of value

Since the year 2000, the value of money in the UK has steadily deteriorated, a trend largely driven by the government's monetary policy decisions. Inflation, the persistent rise in prices, has eroded purchasing power, meaning the same amount of money buys less over time. The Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has aimed to keep inflation low and stable, but its actions—such as interest rate adjustments and quantitative easing—have often fallen short of this goal. For instance, inflation peaked at 11% in 2022, forcing the MPC to hike interest rates to curb price rises. However, these measures have had mixed results, with inflation only gradually falling back toward the 2% target in recent years.4 Additionally, unconventional policies like quantitative easing have contributed to sterling depreciation, further weakening the currency's value.

Lets further explore how UK monetary policy since 2000 has fueled inflation, devalued the pound, and left consumers grappling with the long-term consequences of diminished purchasing power.

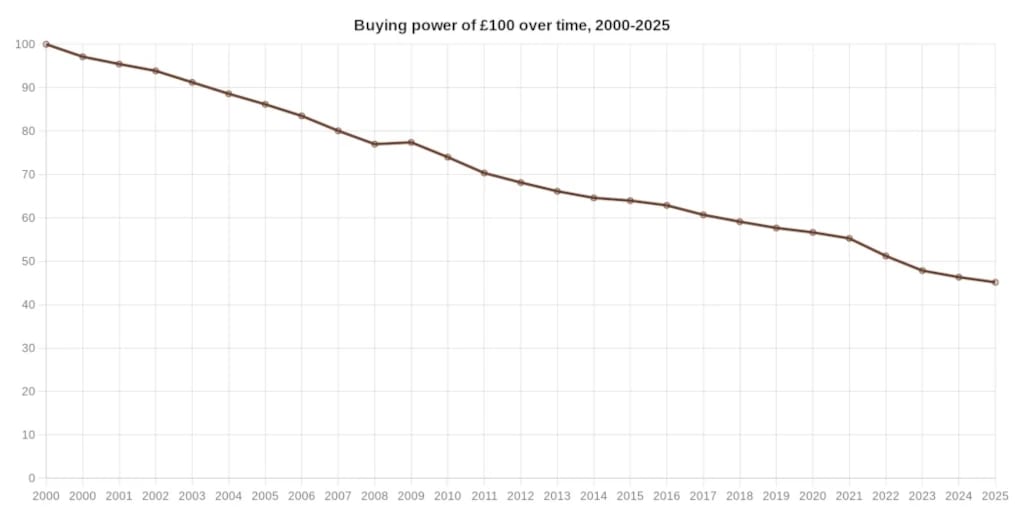

How the value of £100 has deteriorated from 2000 to 2025

At the turn of the millenium, £100 would've purchased the equivalent purchasing power as £215.11, at the time of writing. Essentially, that is an increase of £115.11. This primarily due to the fact that the pound has had an average inflation rate of 3.11% per year between 2000 and 2025, which has produced a cumulative price increase of 115.11%

If we work this backwards, what this means that today's prices are 2.15 times as high as average prices since 2000, according to the Office for National Statistics composite price index. In monetary terms this works out too that a pound today only buys 46.488% of what it could buy back then.

UK Monetary Inflation

Inflation is the rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, and subsequently, the purchasing power of currency is falling. When inflation occurs, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services.

Each month, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) collect around 180,000 prices of about 700 items. They use this shopping basket to work out the Consumer Prices Index (CPI). CPI is the measure of inflation that the Bank of England targets.

It is typically expressed as an annual percentage change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which measures the average price change over time for a basket of consumer goods and services. For example, if the inflation rate is 5%, it means that on average, the prices of goods and services that consumers typically buy have increased by 5% over the last year. This effectively means that your money's value has decreased by 5%, as you now need to spend more to purchase the same items.

The UK Government sets a 2% Inflation target

An inflation target of 2%, has become a standard target for most major central banks including the Bank of England, the U.S. Federal Reserve, and the European Central Bank. The figure itself is not derived from any rigid scientific formula. Instead, it emerged from a combination of economic theory, historical experience, and international consensus over several decades.

The UK’s inflation targeting regime was born following its departure from the European exchange rate mechanism in 1992, when the UK needed a nominal anchor for the price level. Initially the Chancellor imposed an inflation targeting range of 1.0%-4.0% which later became a 2.5% target based upon RPIX - an alternative measure of inflation.

It wasn’t until 2003 when inflation targeting as we know it came into being. The CPI inflation rate became recognised as the better measure of price changes, however, because of difference in the methodologies, CPI historically ran lower than RPI. So, in December 2003 the Chancellor set a CPI inflation target rate at 2%.

The Bank of England was given its 2% inflation target in December 2003, when the Consumer Price Index (CPI) replaced the Retail Prices Index (RPI) as the official measure of inflation, and the target was formally set at 2%.

It is often perceived as important to have a degree of inflation within an economy, primarily because it viewed as a signals of growth, employment, rising wages and without it consumers may put off spending into the future in the expectation of lower prices and reduce demand now. However, if if inflation is too high or is volatile, it’s hard for households to plan spending and difficult for businesses to set prices and wages.

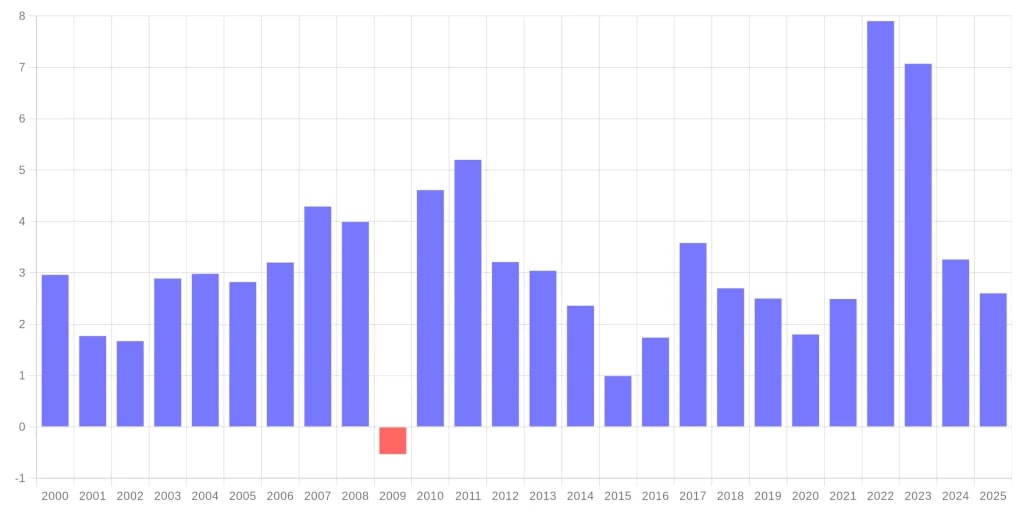

The chart below illustrates just how unsuccessful the Bank of England has been in achieving the arbitrary 2% target.

The astute will notice, that despite the Bank of England only been given the arbitrary target of 2% in 2003, inflation kept steadily well above the 2% target and even grew to double its intended target. Then the 2008 Great Financial Crash happened, and in response to that the Bank of England embarked on a long period of low interest rates and introduced unconventional policies like Quantitative Easing (QE), where it digitally creates money to buy government and corporate bonds to stimulate the economy. While these measures were designed to support growth, they expanded the money supply and contributed to a long-term environment of rising prices or as we have come to know it as Inflation.

The real & true effects of inflation is that it erodes the purchasing power of money, which means your money buys fewer goods and services over time as prices rise.

What are Interest Rates

The only tool that the Bank of England, and most Central banks across the globe, have to fight inflation is Interest Rates.

an interest rate is the cost of borrowing money or the reward for saving it. It is typically expressed as a percentage of the principal amount (the original amount of money loaned or saved).

Interest rates work in two ways:

- For a Borrower: If you borrow £1,000 at a 5% annual interest rate, you must pay back the original £1,000 plus an additional £50 in interest over the year. The interest rate is the price you pay for using someone else's money.

- For a Saver: If you deposit £1,000 in a savings account with a 2% annual interest rate, the bank will pay you £20 in interest over the year. The interest rate is the reward you get for letting the bank supposedly use your money. (More on this later)

The most important interest rate in an economy is the Base Rate. This is the rate at which Bank of England lends money to commercial banks. It acts as a benchmark that influences all other interest rates in the economy, from mortgage rates and car loans to the interest on your savings account.

How do interest rates help fight inflation

The Bank of England uses Interest Rates as their primary tool to combat and control inflation. When inflation is too high, the central bank will raise interest rates. This, in theory, is supposed to set off a chain reaction designed to cool down the economy and reduce the upward pressure on prices.

The expected process supposedly needs to have the following effects on the economy.

Make Borrowing More Expensive

When the central bank raises the Base Rate, commercial banks follow by increasing the interest rates they charge on loans (mortgages, credit cards, business loans, etc.).

- For Consumers: Higher mortgage and loan repayments leave households with less disposable income. This discourages big-ticket spending on things like houses, cars, and home renovations.

- For Businesses: The cost of borrowing to invest in new machinery, factories, or expansion projects goes up. This makes businesses more cautious and likely to delay or cancel investment plans.

Result: Both consumer spending and business investment, which are key components of economic demand, start to slow down.

Encourage Saving Over Spending

Higher interest rates also make saving more attractive. If the interest rate on a savings account rises significantly, people are more incentivised to save their money rather than spend it.

Result: A higher propensity to save further reduces overall spending in the economy. Less money is chasing the available goods and services.

Reducing Demand to Relieve Price Pressure

Inflation is often described as "too much money chasing too few goods." By making borrowing expensive and saving rewarding, higher interest rates directly reduce the amount of money circulating and being spent in the economy.

With less demand from consumers and businesses, companies lose their ability to keep raising prices. To attract the remaining customers, they may even have to slow down price hikes or offer discounts to sell their products.

Result: The overall rate of price increases—inflation—begins to fall back towards the central bank's target.

Strengthening the Currency

Higher interest rates can also help fight inflation by attracting foreign investment. When a country's interest rates rise, investors can get a better return on assets held in that currency (like government bonds). This increased demand for the currency causes it to appreciate against other currencies.

A stronger pound makes imports cheaper. Since many of the goods we buy in the UK are imported (e.g., food, fuel, raw materials), cheaper imports directly lower the cost of living and put downward pressure on inflation.

The Trade-Off: The "Brake" on the Economy

It's crucial to understand that using interest rates to fight inflation is not a painless process. If the economy is a car, inflation is it speeding too fast, and raising interest rates is slamming on the brakes.

While this slows inflation, it also slows down the overall economy. This can lead to:

- Slower economic growth.

- Higher unemployment as businesses cut back on expansion and hiring due to lower demand.

- Increased pressure on borrowers who struggle with higher loan repayments.

Therefore, central banks must constantly balance their fight against inflation with the need to avoid causing a deep recession. They are trying to slow the economy just enough to tame prices without bringing it to a complete halt.